A Primer on Surveillance Issues in the Disability Community

As privacy activists, we’re often called on to suggest alternatives to technologies that spy on us and sell our data. For disabled people, opting out of data sharing isn’t always the best choice. Sometimes that choice is taken away from us. What happens when the network effect is the difference between getting support and being alone with some tough decisions? For many disabled folks, this is our reality:

Many times you find yourself having to give up your data in order to live, study, and move around in society

Your needs for assistive technology are met by big tech companies

Bureaucracies use artificial intelligence and surveillance to deny you support needed to participate in your community and even survive at all.

Stuck Between Privacy Activists & Big Tech

Disabled people are stuck between privacy activists who ignore accessibility and different technology needs, and big tech companies that use disabilities as marketing for surveillance tech. In order to build better options, it’s important to think about privacy in terms of what a technology offers and the harms that can result when disabled people are the users or targets of surveillance technology. Since disabled people are also creators of technology, accessibility in anti-surveillance work isn’t something bestowed upon a passive group. It’s a vital practice of inclusion that deepens our understanding of technology and justice.

The Network Effect

Disabled people have reasons to share more data. Getting a diagnosis is the first step to getting accommodations and treatment. This isn’t always easy. Doctors may be racist, sexist, and fatphobic, telling patients that illness is all in their heads, and refusing to do further investigation. People with a mental and physical illness experience heightened levels of this sort of discrimination.

Fighting for a diagnosis is physically, mentally, and economically taxing on top of symptoms that may include pain and fatigue. The average time to diagnose some conditions can be years, especially if they primarily affect women.

Avoiding Social Media is a Luxury

Support on social media can make a difference in medical treatment. Patients inform each other about the tests that need to be run and how to get doctors to listen. Since the stakes are so high, it’s important to go wherever the people like you are gathering. Avoiding social media is a luxury that chronically ill and disabled people don’t have.

Some disabilities are more social than medical. The disability is a result of decisions made by society about architecture, social norms, and ways of doing things that exclude people. Social media provides support here too. #JustAskDontGrab started when Dr. Amy Kavanagh, who has a visual impairment, shared her experiences of being grabbed by people after she started using a cane to help with mobility. Wheelchair users shared safety tips, including spikes for wheelchair handles that discourage people from moving them without consent. Social media is a source of peer support and a forum for creativity.

Disability Surveillance: A Mixed Bag

Surveillance isn’t always harmful. Context and consent matter. Research is a form of surveillance. Knowing how many people are disabled is useful for planning accessibility. Documenting a disability can enable accessibility. Insurance companies, schools, and employers require personal data to prove eligibility for accommodations and support. If a disability results from a rare disease, people may choose to offer their genetic data and medical records to researchers. They may take part in studies that could lead to better therapies and less pain.

Some forms of surveillance have justifications, but veer dangerously close to violating the rights of disabled people to privacy and autonomy. A California judge mandated increased surveillance, including body-worn cameras for guards, in prisons where guards abused disabled incarcerated people. Surveillance, including recording devices in bedrooms, are used in care homes in order to monitor potential abuse, self-harm, and medical needs. Not all of these devices can be turned off by residents.

Surveillance as a Way to Deny Benefits

Meanwhile, surveillance in order to deny benefits is also a reality. The ways that governments and insurance companies check for eligibility are invasive and inaccurate. Insurance companies hire private investigators who follow people who filed claims after being injured in the workplace. Monitoring of social media by these investigators means disabled people must self-censor or risk their ability to pay bills and get medical care. Ambulatory wheelchair users or people with energy-limiting chronic illnesses can’t post pictures that show a moment when they have more energy and less pain.

In the UK, the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) is particularly aggressive, combining data from social media, CCTV cameras, businesses with disabled people as customers, and other government departments to deny benefits. Disability activists who protest are surveilled by police, who pass their data on to the DWP. The message is clear: protest, and you risk access to your rights as a disabled person. The DWP runs campaigns encouraging neighbors to spy on disabled people.

In the US, the Electronic Visit Verification requirement for caregivers paid by Medicaid intrudes on the lives of disabled people with geofencing and biometric surveillance. Caregivers aren’t paid for work outside their clients’ homes, restricting the movement of disabled people and violating their human rights. Disabled people do not have marriage equality. Getting married results in loss of benefits. Some people divorce in order to secure healthcare for a disability acquired after marriage. Some governments conduct surveillance to make sure these couples aren’t living together. Anti-surveillance technology must be accessible.

Loss of Privacy: Boundary Violations

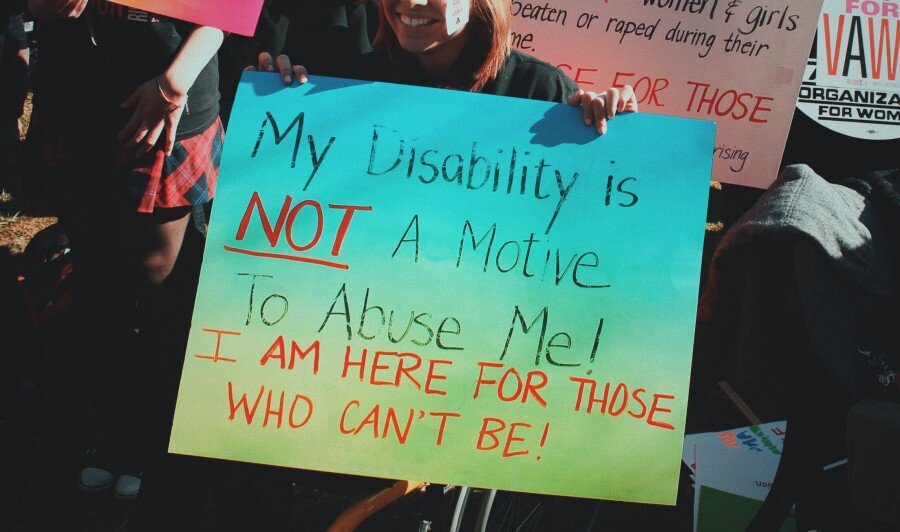

Loss of privacy doesn’t just come from companies and governments. To be disabled is to experience boundary violations from non-disabled people who feel entitled to the time, space, and stories of disabled people.

Videos of disabled people posted on social media by non-disabled people they don’t know personally are one example. The people in the video are just going about their day, but they are displayed, without consent, as inspiration because they have “overcome” their disability.

Comedian and journalist Stella Young described this as “inspiration porn”. Non-disabled people protest that they mean well, but it’s still a violation of privacy.

Other interactions with strangers are more aggressive, even dangerous. The attitude, encouraged by governments and companies, that disabled people are taking advantage of the system, causes harm. People with invisible disabilities are harassed when they use accessible parking spaces or priority seating on public transportation. People who use mobility aids but don’t move in ways that non-disabled people consider disabled enough are harassed online. There are forums dedicated to harassing disabled people. Non-disabled people post pictures of people they think are faking.

This practice intersects with other marginalizations. Disabled women are more likely to experience harassment, violence, and stalking. Any technology made to protect privacy must be accessible.

Disability as Surveillance Marketing

I was at a conference a few years ago where civil society, governments, and corporate representatives gathered to discuss internet governance. A panel on disabilities featured people from corporations. One representative from a company that makes smart speakers showed a video of an autistic kid using a smart speaker to remind him about routine tasks. His parents worked for this company. The man who played this video couldn’t answer any questions about the number of disabled people employed in any capacity at the company, let alone in departments staffed by designers of technologies that double as assistive tech.

The Rise of Accessibility in Tech?

On the bright side, accessibility is being built into more devices. Screen readers help people with vision impairments. Speech to text helps people with motor disabilities or joint problems. Voice assistants and home automation can help people control their living spaces when switches aren’t accessible. Captions are becoming more widespread, even though automated captions aren’t always accurate. Apps can help track the causes of painful flares of chronic illnesses. Health trackers can alert people to acute health issues, and convince doctors to run tests and offer treatment. To-do apps, calendars, and location-based reminders can help with executive dysfunction.

There are tradeoffs with these devices and software. They often violate the first guideline of working for disabled people: nothing about us without us. If the benefits to disabled people are an afterthought or pointed out by the marketing department, the potential harms won’t be examined thoroughly. Some things marketed as assistive technology are really disability dongles, a piece of design that is dreamed up by non-disabled people without consulting the people who would use it. Even if it fills a need of disabled people, technology provided by many for-profit companies gathers data for advertising. If adtech takes the place of other assistive tech, are disabled people given the opportunity to freely consent to data gathering? When privacy advocates say these devices aren’t necessary in any case, they are dismissing the concerns of disabled people who also care about privacy. We need to build alternatives.

Surveillance Amplified

Some technologies that harm everyone are particularly harmful for disabled people. Automated proctoring software used to catch cheating on tests during remote learning was designed with bio- and neuro-typical white people as models. Moving differently or having other access needs flags disabled people as cheaters.

People with mental illnesses are more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators, but surveillance for law enforcement purposes targets people with mental illnesses.

A database for use in Florida schools marketed as a tool for prevention of school shootings is opposed by privacy and disability activists. These tools, combining social services, police, and social media data, target students with disabilities. In addition to being unfit for the stated purpose, they are harmful.

Discouraging people from seeking support for mental health issues, or demanding action when they are being bullied for being disabled, is already bad enough to warrant a halt to this program. Being flagged for attention by law enforcement is also dangerous for disabled people. Up to half of the people killed by police in the US are disabled, and yet one solution proposed in Connecticut is more surveillance of disabled people.

Digital Rights Defenders Need to Educate Themselves on These Issues

Anti-surveillance activism intersects with disability activism in many ways. The violence that surveillance enables targets disabled people and results in disability for previously non-disabled people.

Many of the people that digital rights communities work with have ties to disability beyond the likelihood that about 1 in 5 people you meet may be disabled.

Journalists get injured, and may need accessibility in tools for secure communication in order to continue their work. Environmental activism is dangerous, making activists targets of corporations and governments, and yet people put themselves at risk to safeguard the health of their communities. This is disability activism, as well as a reason to use privacy-enhancing technologies. Calls for prison abolition and defunding the police are disability activism, and the people doing this work face massive amounts of surveillance.

The digital rights community must educate themselves on these issues. We need to ensure we are truly building tools and strategies that work for various forms of surveillance. We must understand the specific contexts. The work isn't done until it’s accessible.